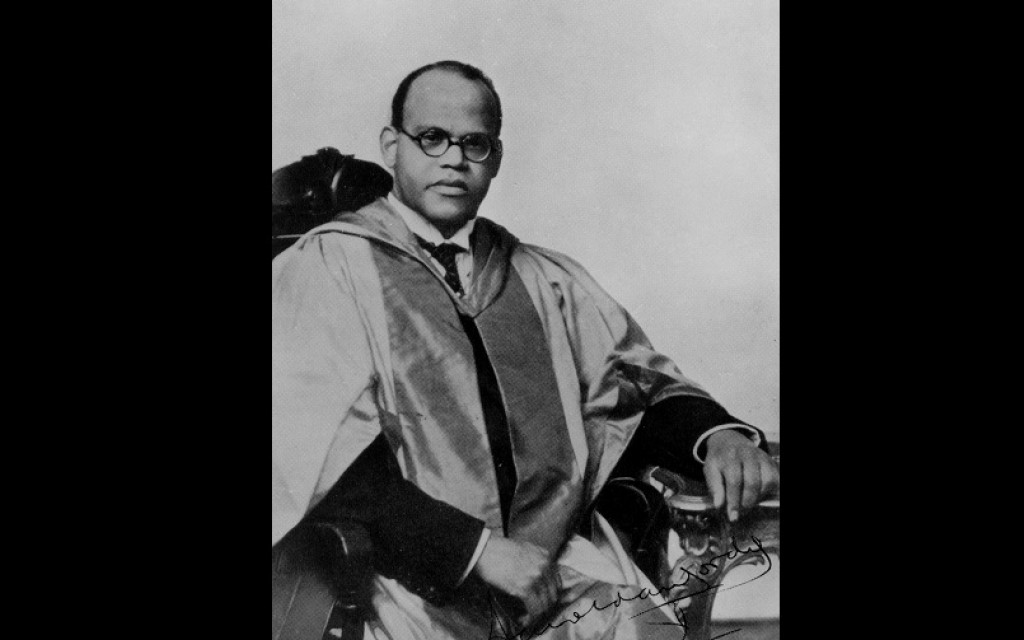

Rejected because of the colour of his skin

Dr Moody was completely unprepared for the racism of Edwardian London and found it difficult to find lodgings and other students didn't speak to him. Despite winning many prizes and graduating at the top of his class in 1910, he was denied a hospital job because the matron refused to "have a coloured doctor working at the hospital". Although he was the best qualified candidate, he was also rejected for the post of Medical Officer for the Camberwell Board of Guardians and he was told that he would be unsuccessful in his profession as people did not want to be treated by a Black man.

After an unsuccessful three-year search for employment, in 1913 Dr Moody established his own GP practice in Peckham. At this time healthcare was costly and many were forced to go without, but Dr Moody treated children in the area for free and opened his home to Black travellers denied lodgings elsewhere.

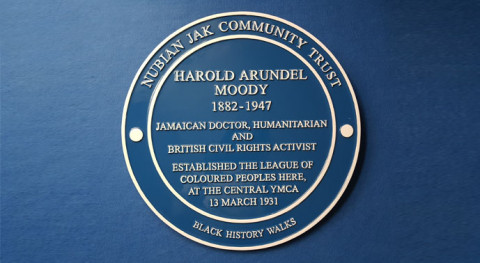

Forming the League of Coloured People

In 1931, after WW1, race relations in the UK grew evermore tense and Dr Moody became increasingly mindful of the discrimination going on throughout the country. This is when he formed the League of Coloured Peoples with the help of other young, black men who were living and studying in London at the time, who later became famous in their own right. This group included Jomo Kenyatta - the first President of Kenya, Paul Robeson – the Singer, Actor and star Athlete who studied at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies and world famous Cricketer, Learie Constantine. Together they actively fought for equality, with defined the following aims for the League:

- To promote and protect the Social, Educational, Economic and Political Interests of its members

- To interest members in the Welfare of Coloured Peoples in all parts of the World

- To improve relations between the Races

- To cooperate and affiliate with organisations sympathetic to coloured people

In 1937, a fifth aim was added:

- To render such financial assistance to coloured people in distress as lies within our capacity

The League of Coloured Peoples publish its own journal called 'The Keys'. It became a powerful medium which discussed racial segregation, work place prejudice, the ill-treatment of black nurses and discrimination against black children during the evacuation of World War 2.

Dr Moody's work included fighting for the lifting of the colour bar in the British Armed Forces, fair wages for Trinidadian oil workers and employment rights for black seamen. Dr Moody was eventually appointed to a government advisory committee on the welfare of non-Europeans in 1943.